We’ve recently started studying the Great Migration, the exodus of over 6 million black people from the harsh realities of the South to the uncertain promised lands of the North. The Great Migration happened in two phases, from 1910 to 1940, and 1940 to 1970. I now know my maternal grandparents and my paternal grandfather were a part of that second wave. My paternal grandmother’s parents were a part of the first wave.

Learning about the early migrations of other great-great aunts and uncles in the 1920s also fleshes out the family narratives. It’s interesting to reflect on the imprints of possibility both my grandfathers would have internalized about the North. As little boys growing up in different parts of North Carolina, seeing their family members head North opened up doors for futures yet to be realized. Their knowing that the world outside of their small towns could also be theirs too changed the course of all of our lives to come. The more we uncover about this pivotal moment in American history, and where our family stories intersect with it, the more fascinating it is to comprehend that I exist at all.

For a long while now I have been marveling at how my own birth was set in motion so many generations ago, and from disparate lands across the globe. Decisions made by great-grandparents and their parents, tribes of people unknown to each other, yet all conspiring in some way towards the makings of me. So far I have proof of my beginnings in North Carolina, Georgia, New York, Jamaica, and the ever-present, geographically ambiguous certainty that once upon a time, before the transatlantic slave trade, my ancestors came from multiple regions of Africa. There are also high probabilities that some cells of mine began in Scotland, and that at least one strand of my mother line is Cherokee. Still, I feel, I know, all of me is beyond what is provable, and there are many more places on this Earth that I can also call home.

Bloom and I are simultaneously researching our roots. Our stories are shared and also divergent in so many ways. My parents were born in the same year, in the same country, and met in junior high school when they were 12 years old. In great contrast, I met James only 3 years before Bloom was born. Our mothers gave birth to us a decade apart, each on her own continent, separated by customs and language, by ocean and time.

Already, me and Bloom’s pathways into our distinct human forms are worlds, galaxies apart. Naturally as his mother, Bloom’s story contains all of my origins, but my story could never hold all of his. An entire realm of his existence extends beyond anything I know. I have no choice but to learn who else he is, who else all my children are.

Mapping the ways of our individual and collective creations means revisiting the routes that brought us to this now. It means looking back to the moments of rupture and undoing, of chance encounters and perfect timings. It means naming the tragedies and the blessings that collaborated in the forces that brought us together as a family. It means tracing the choices of ancestors—those with names and those without—remembering their nuances, imagining their prayers, and filling in all the gaps with our intuitive brilliance. Or maybe, as has happened for so long, it means leaving the gaps in tact, soft, empty, and unscripted for the next generation to interpret and author as they will.

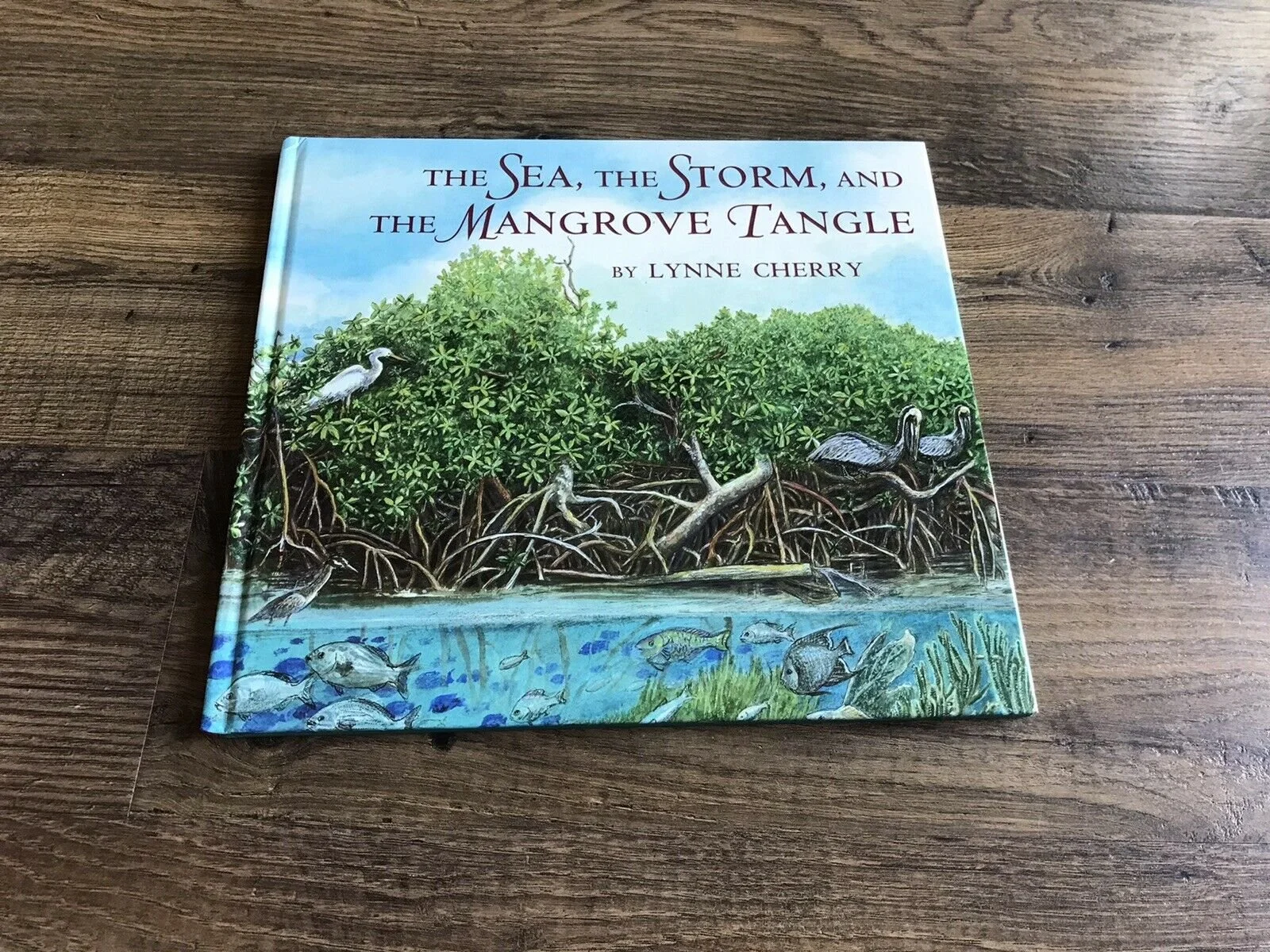

We got only as far as the opening paragraph in our first reference material for the Great Migration before we had to stop and rewind. “Who is Jim Crow,” Bloom asks. And that opens up another dimension I hadn’t fully anticipated. I should have, though. How else to explain the terror so many black people were escaping without framing it within the brutal, post-Civil War environment of the South? How else to convey the significance of these long-ago migrations that directly shaped the part of his life he gets from me without painting the whole picture?

What is the whole picture, really? Is it possible to ever know it all? Is the journey worth taking even if it sparks more questions than it answers? I feel it is.

In this first week of attempting to help Bloom understand the complexities of the Great Migration, we have come to other critical research questions inspired by current global migration movements, Bloom’s father’s family’s immigration stories from East Africa, my family’s immigration from Jamaica on my father’s mother’s paternal grandparents’s side, and the family journeys we know about from others in our community. Every story requires pulling up multiple maps, looking up historical records, re-examining the timelines of a war, combing through the dense layers of humanity’s becoming, each horror and each triumph illuminating something essential all the same.

“How did you get to America?” Bloom’s question erupts like a spring in the wilderness of our explorations, an opening to a universe yet unexplored amidst the laptop, notebooks, dictionaries, books and atlases strewn across my bed—my preferred “classroom” most days. Our dialogue about why black people started fleeing the South a century ago led us into talks about the risks so many people take today to leave their home countries in search of a better life, oftentimes in America or Europe. He’s trying to wrap his nearly 10-year old mind around the idea that sometimes people do leave home, and everyone and everything they know, and never return.

“I was born here,” I say automatically, “and so were you.” But as soon as I say it, I know it’s not true. And this knowing brings me pause. Simply being born here doesn’t explain the why, the how. It is in this moment that I feel something magical can come from our research, something bigger and brighter than merely coloring in the branches of our own family trees.

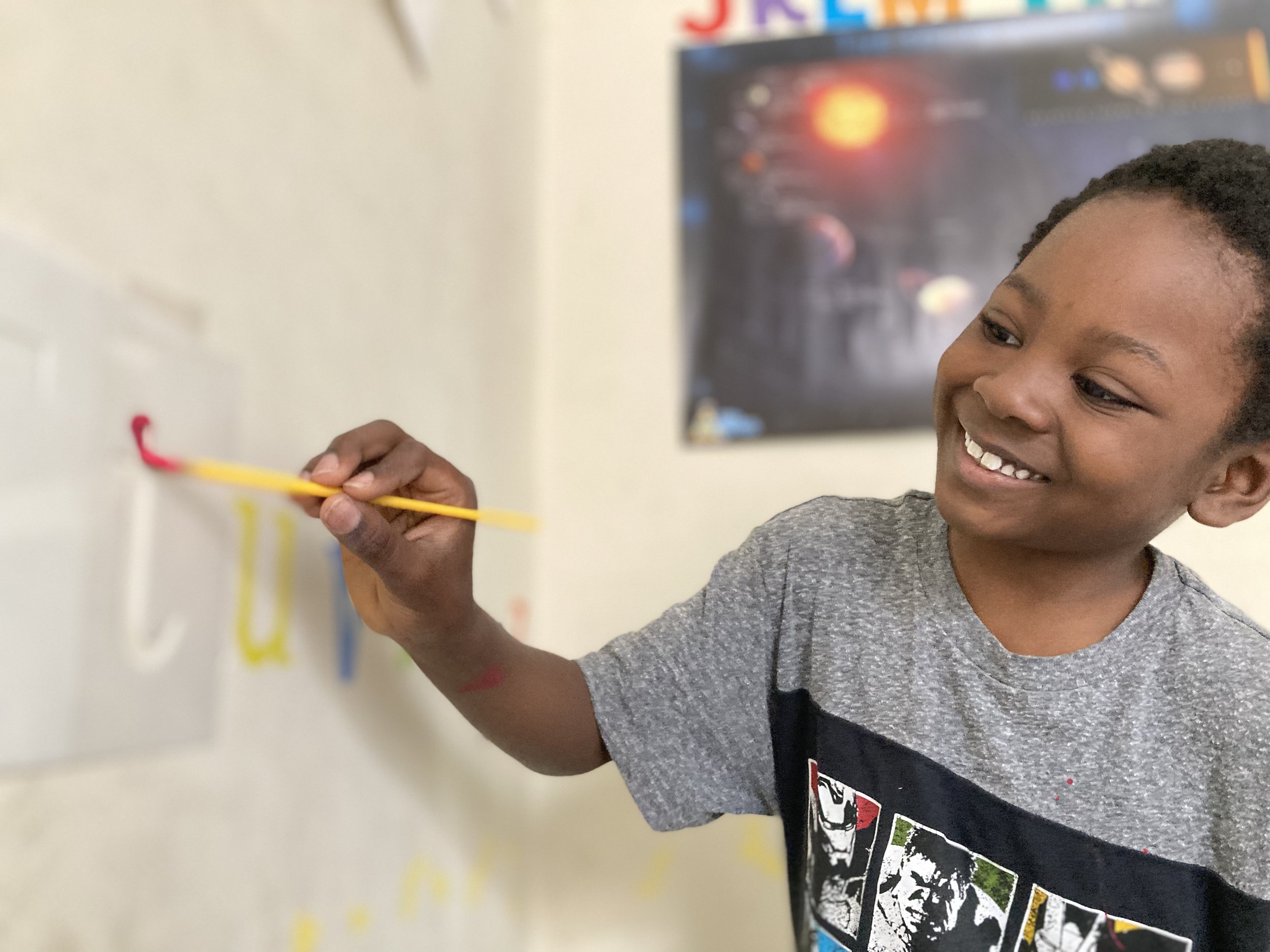

I see this beautiful possibility of sharing the experiments and labors of discovery with our family and learning village. I’ve been dreaming up a community story creation practice for so long, and slowly positioning Wildseed to be the space where we grow these programs for our community. I see that even if we have intimate moments of researching as mother and son, Bloom and I don’t have to venture into these terrains alone. There’s something healing and powerful about creating a communal space for more families to do this work together.

The Great Migrations family story collage project is a seed that has been activated from our preliminary studies about the Great Migration. I added the “s” because it’s not just going to center stories about black Americans moving from South to North, but also the multitudes of migrations powered by people of the African Diaspora. This is both a personal necessity—because my children carry multiple black migration stories in their blood—and also a community invitation because I do believe there are more opportunities for us to genuinely connect and commune as a human family, in the gathering and sharing of our stories, in the sorting and sifting of our memories and dreams. This budding idea is just the beginning of another journey. Where will it take us this time?

Cover Photo Story: Once upon a Mommy, almost 2 moons along with Bloom

Photo by Colin A. Danville